Use and the Art Experience

by Rob Barnard

Published in Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 5, 1991, 3-8.

There is a perception in the modern craft world that anyone interested in useful craft is some sort of neo-conservative romantic who wishes culture would revert to a pre-industrial lifestyle. He or she is considered to be out of touch with modern sensibilities and thought to be either unable or unwilling to address contemporary concerns. Critics of useful craft, however, have never really articulated what these concerns are, but instead have adopted a formula that says if an object is useful it belongs to the past and is therefore unsuitable to convey modern feelings. This presumption about useful craft's inefficacy in modern culture is not based on any kind of intellectual or philosophical examination of the possibilities this form of expression offers. Its rejection by the modern craft establishment has more to do with the fact that useful craft runs contrary to all the values manifested in the postmodernist, avant-garde, market-oriented climate of the fine arts world--a world after which modern craft has mindlessly modeled itself.

Photo by Dennis Siporsky

All pottery photos by Hubert Gentry

Pitcher 20 cm/h

It was at this time that I was introduced to the writings of John Cage and was immediately attracted to them. I believed, like Cage, that the artist should live on the frontier of his art and should challenge culture's preconceptions, but at the same time I worried that my interest in pottery--which everyone in my own culture seemed to agree was an anachronistic endeavour--placed me in a category of artists who, Cage said, "spend their lives with music of another time, which, putting it bluntly and chronologically, does not belong to them." Things came to a head after I attended a performance by Cage and Merce Cunningham in Kyoto. Cage used common everyday objects with microphones attached to them for instruments but the music itself was anything but mundane. It gave a timeless and mysterious feeling you would associate with primitive music and yet there was no question about its modernity. In his performance, Cunningham rejected the athletic leaps and other complicated physical movements of classical dance in favour of ordinary body movements like reaching and bending. At one point he merely walked diagonally across the stage, but with such presence and authority that I found myself questioning my whole notion of walking.

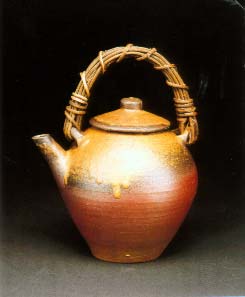

Teapot 25cm/h

It started me questioning how the fine arts establishment (not to mention the modern craft world) could accept aspects of the mundane in Cage and Cunningham's work but couldn't accept the proposition, for example, that an ordinary cup couldn't be used to create that same kind of art experience. I went back and reread more of Cage's writing to find either an explanation for this obvious inconsistency or an intellectual argument to support my belief that pottery was in fact capable of such a feat. I found my answer in his Defense of Satie delivered at Black Mountain College in the summer of 1948. Music, he said, in order to be distinguishable from non-being--that is, pure noise--must have structure; it must have parts that are clearly separate but that interact to make a whole. He continued: "We are left with the question of structure, and here it is equally absurd to imagine a human being who does not have the structure of a human being, or a sonnet that does not have the relationship of parts that constitutes a sonnet. There may, of course, be dogs rather than human beings--that is, other structures--just as in poetry there may be odes rather than sonnets. There must, however, as a sine non qua in all fields of life and art, be some kind of structure--otherwise chaos. And the point here to be made is that it is in this aspect of being that it is desirable to have sameness and agreed-upon-ness. It is quite fine that there are human beings and that they have the same structure. Sameness in this field is reassuring. We call whatever diverges from sameness of structure as monstrous.''1

Wine Bottle 23cm/h

Besides structure, Cage insisted that music comprised three other elements: form, method and material. To continue the analogy with human beings, while each one of us shares the same structure, the form of our life--what we do with it--varies with individuals. Method in life is, at its most simplistic level, eating, sleeping and working. How one goes about these tasks varies. The last element, material, is physical. Within our common structure we all have physical differences and accommodate, even accentuate those differences. These elements, Cage says, historically have varied in music and are and make it interesting, but structure is fundamental.

The structure of crafts, that which makes its form, method and material interact as a whole and separates it from other structures like painting and sculpture, is that it was made to be used.

In the field of structure, he argues there has been only one new idea in European music since Beethoven whose compositions were defined by means of harmony. That idea is found in the work of Anton Webern and Erik Satie whose compositions are defined by means of time lengths. The common denominator of music throughout all of history and all cultures is that it has a beginning and an end and that the sound is punctuated by moments of silence. Cage insists that there can be no right making of music that does not structure itself from the very roots of sound, silence and their duration. Beethoven's influence, Cage concludes, "which has been as extensive as it is lamentable, has been deadening to the art of music."

I could hardly believe I could ever find myself agreeing with Cage about Beethoven's influence but his arguments seemed so soundly based that I couldn't help but be swayed. I began wondering if I couldn't apply his methodology to the crafts. Form, method and material were all evident aspects of craft but, as in other disciplines, varied in their application. But what did all crafts throughout history have in common; what was, in other words, its structure--its historical agreed-upon-ness? The inescapable conclusion was usefulness. The structure of crafts, that which makes its form, method and material interact as a whole and separates it from other structures like painting and sculpture, is that it was made to be used.

Dish 30cm/diameter

There is even a parallel in crafts to Beethoven in music. Someone whose work, like Beethoven's, I admire but whose influence has put modern American craft--to use Cage's words--on an "island of decadence", is Peter Voulkos. Voulkos's emphasis on the object as a self-sufficient aesthetic entity untainted by concerns of function and his flawed perception that he was breaking new ground and challenging a worn-out tradition, pushed craft away from the structure that had made it viable and understandable for thousands of years and replaced it with an ethnocentric aesthetic of barely 20 years. In a well-meaning but seriously flawed argument in a 1961 issue of Craft Horizons, Rose Slivka supported this shift of structure from craft to painting. "In the past, pottery form," she wrote, "limited and predetermined by function, with a few outstanding exceptions, has served the freer interests of surface.''2 She went on to list three extensions of clay as paint in contemporary pottery: the pot as canvas, the clay as paint, and form and surface opposing each other with colour defining, creating and destroying form. Voulkos's work and the critical constructs that reinforced it put modern craft on a course of diminishing returns yet to be corrected.

Each of these disciplines--painting, photography and craft--has its own structure and responds to cultural change by building on structure, not abandoning it.

The analogies between craft and painting have continued. Vicki Halper in her catalogue essay for the exhibition Clay Revisions: Plate, Cup, Vase, says, "The potter's dismissal of function as a governing premise in the construction of vessels is analogous to the painter's and sculptor's abandonment of realism early in the 20th century. In each case industrialism and technology left their mark: photography created cheap perfect images and mass factory production created cheap perfect forms. This allowed for a separation between traditional craftsmanship and the expression of ideas and feelings in both ceramics and the fine arts.''3 There is no question that painting, at its most mundane, was used purely as a vehicle for representation--the same can be said of photography today--but painting, at its best, was never about mere representation. One could hardly suggest, for example, that Rembrandt's or Michaelangelo's works could be replaced by photographs or that, for that matter, the new medium of video can replace the photographs of Walker Evans or Andre Kertez. Each of these disciplines--painting, photography and craft--has its own structure and responds to cultural change by building on structure, not abandoning it. Modern craft, in its desire to achieve cultural status, however, has rejected its structure, and has been busy trying to construct an ersatz structure from elements of craft's history that fit its agenda.

It is difficult to convince someone that use can be a significant factor in the art experience when few people have actually discovered it for themselves. Unless one has been deeply moved to the point that one's life has been changed, then the belief in the notion of art is an act of faith. It wasn't until I attended my first tea ceremony in Japan that I actually felt the power that use has when it is applied artistically to mundane circumstances like eating or drinking. In the introduction to Kaiseki: Zen Tastes In Japanese Cooking, Seizo Hayashi, chief curator of ceramics at the Tokyo National Museum, discusses the tea ceremony and kaiseki--the meal that precedes it. "Creating an atmosphere free of the cacophony of everyday life means more than just creating a brief, happy retreat in a little house. This momentary freedom from everyday cares imposes on those who share it the responsibility of fully utilizing the experience, of being more conscious of their surroundings, of being more fully present and more fully alive during the serenity of the tea ceremony than is possible in the overstimulated world of daily routine. Kaiseki is designed to both aid and provide a focus for the pleasure of living more quietly and more deeply than usual, and hopefully, to have some of this experience overflow into daily life.''4

Cream and Sugar Containers 10 cm/h

In the hands of the serious and questioning craftsperson, the dynamics of use can make art both accessible and participatory, and by doing so re-establish it as a meaningful and potent activity in our culture. To quote Cage again: "The meaning of something is in its use, not in itself."

For far too long, we in the craft field have believed that function is what holds us back in our struggle for cultural recognition. It never seems to have occurred to us that culture, as represented by the fine art world, might be wrong about its dismissal of this aspect of craft. Or more to the point, that this dismissal might, perhaps, be our fault for not understanding the importance of use and exploiting it to its fullest potential, instead of trivializing and denigrating it. In the hands of the serious and questioning craftsperson, the dynamics of use can make art both accessible and participatory, and by doing so re-establish it as a meaningful and potent activity in our culture. To quote Cage again: "The meaning of something is in its use, not in itself."

Notes:

1. John Cage, "Defense of Satie", John Cage, Richard Kostelanetz,

(Praeger Publishers, Inc. 1970)

2. Rose Slivka, "The New Ceramic Presence", Craft Horizons,

No. 4, 1961

3. Vicki Halper, Clay Revisions: Plate, Cup, Vase, (Seattle Art Museum,

1987)

4. Seizo Hayashi, Kaiseki: Zen Tastes in Japanese Cooking, Kaichi Tsuji,

(Kodansha International Ltd. 1972)